In Ted Chiang’s short story, Story of Your Life, a few alien ships appear and orbit around the Earth. The aliens (called heptapods, because they have seven lidless eyes that ring all the way around the top of their bodies) send communication devices called looking glasses to communicate with the humans. Louise Banks, a linguist, is called by the military to assist in decoding the alien language. She soon finds that the alien sentence possesses several distinctive qualities that set it apart from English:

- Instead of displaying multiple characters or “words,” the heptapods display a single pattern containing variations, such as extra strokes or flourishes. How the strokes in a given symbol are arranged visually provides the context for understanding how all the parts of the symbol fit together and, thus, its meaning.

- The order of the “words” doesn’t matter. A heptapod sentence is presented as one symbol, and how each constituent stroke in any given symbol is oriented provides the context for understanding the nuance of each expression.

- This way of expressing all ideas simultaneously, rather than linearly, as in human languages, results from the radial symmetry of the heptapods’ physiology. Since their bodies have no front or back, their language doesn’t either.

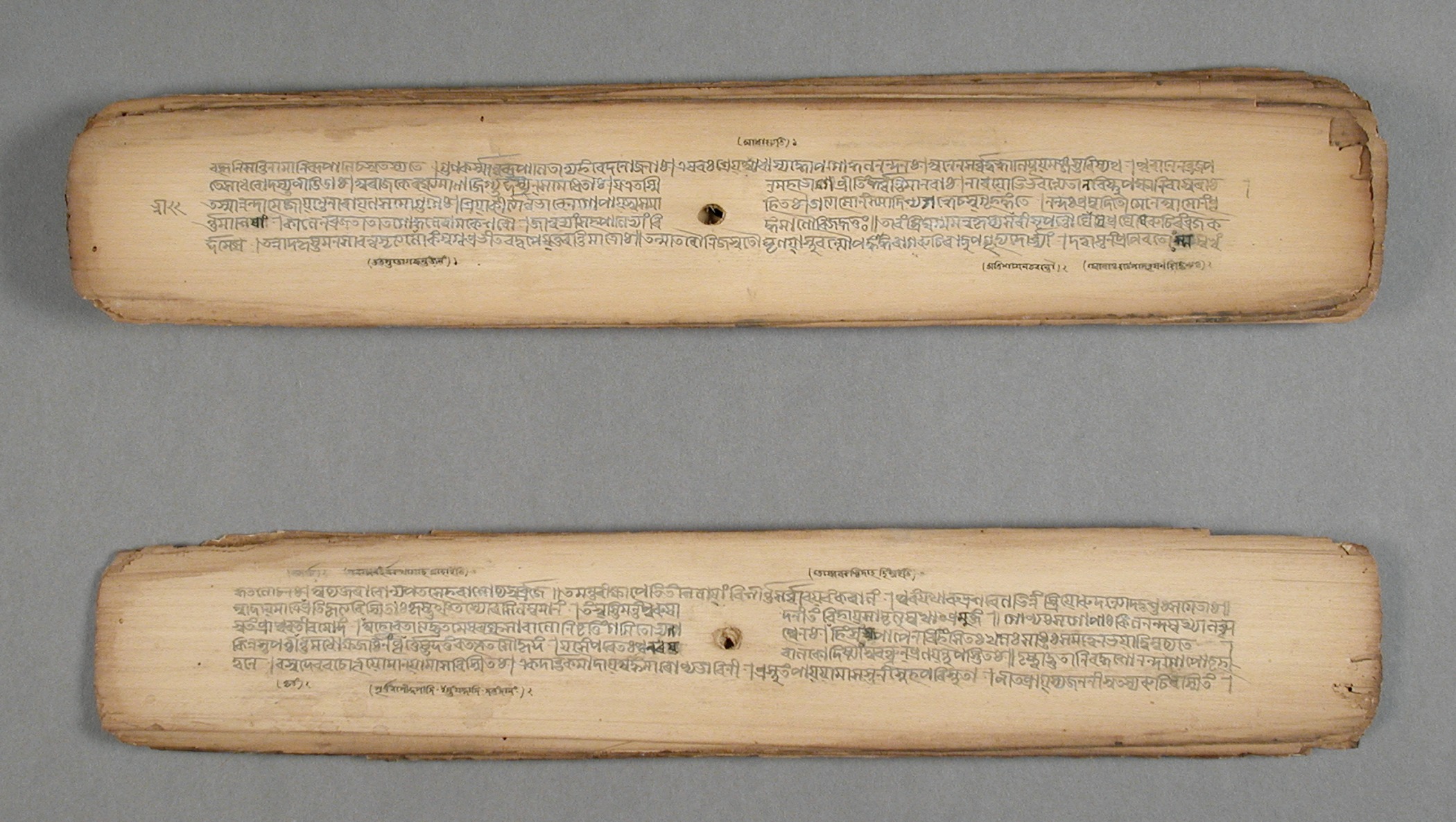

- The writing is semasiographic and independent of speech, like the no-walk or right-turn sign.

While English forces a linear way of thinking, one of the interesting features of Samskritam is that, in a sentence, the order of the words doesn’t matter. You can switch them around, and the meaning remains the same.

For example, a sentence like “Rama is going to the forest” in Samskritam is written as रामः वानमं गाच्छति

It can also be written as

- गाच्छति रामः वानमं

- गाच्छति वानमं रामः

- वानमं गाच्छति रामः

You can’t do this in English. You can’t do “Forest going to be Rama the.” It is possible in Samskritam because the word form changes by incorporating the preposition into it. This process is called vibhakti, and there are 7 types of them. (Technically, 8, but I will exclude Sambodhana from this). You might have mugged it as रामः रामौ रामाः …, but lets see what it means.

Here is a bit of a complex sentence: The boy goes to school from his mother’s home with a friend at 8 am to study.

There are 17 words in this sentence.

The first question to ask is: What is the verb? What indicates action?. That would be “goes.” In Samskritam, that is गाच्छति.

The next question is: who goes? The answer is “The boy”. In Samskritam, it becomes बालकः Since it is the subject, it is in the first vibhakti form बालकः instead of something else. As we look at other vibhaktis, this will become clear what other forms बालकः can take.

Thus, we have a simple sentence: बालकः गाच्छति. (The boy goes).

With the subject and verb sorted out, let’s find out the object. In this case, it is the school or विद्यालय:. Since it is the object, it cannot be in the first vibhakti form विद्यालय:. It will change to the second vibhakti विद्यालयं.

Now our sentence becomes बालकः विद्यालयं गच्छति

Next question: with whom? Answer: with a friend.

A friend in Samskritam is मित्रं . If it is “with a friend,” it becomes the third vibhakti. Thus मित्रं, which is the first vibhakti form of a friend, becomes मित्रेण.

Now our sentence is: बालकः मित्रेण विद्यालयं गच्छति

Next question: for what? Answer: for studying, which becomes पठनाय which is the fourth vibhakti.

Next question: from where? The answer is home or गृहं. But “from” indicates the fifth vibhakti, and hence it becomes गृहात्.

Next question: whose house? Answer: mother’s. Mother is माता. But since this indicates a belonging, it becomes the sixth vibhakti, and the form changes to मातुः

Next question: At what time? Answer: 8 am which is अष्ट वादनम् . Since this represents “at” a time, it becomes the seventh vibhakti or अष्ट वादने

Putting it all together, the sentence becomes बालकः विद्यालयं गच्छति मातुः गृहात् मित्रेण पठनाय अष्टवादने

Thus, 17 words in an English sentence become 8 words in Samskritam. This is because all the prepositions are now part of the word.

We achieve a few things due to this.

The first is compactness. By cleverly combining word endings and cases, Samskritam packs a lot of information into fewer words. In an oral tradition, this makes it easy to memorize texts.

Second, this makes switching the word order and preserving the same meaning easy. Hence our sentence can also be written as बालकः मातुः गृहात् मित्रेण अष्टवादने पठनाय विद्यालयं गच्छति. In English, the sentence follows a linear order. Scramble the words, and the meaning is lost. In Samskritam, poets and writers can play with word order for emphasis, rhythm, or specific effects. It unlocks a non-linear way of thinking and expression, allowing the Samskritam’s beauty to shine.

Finally, with each word complete by itself, we get a good idea of its relationship with other words. For example, when we see the word मित्रेण, it gives out a clue that it is the third vibhakti form of मित्रं and that it has a “with” relationship. Each vibhakti case acts like a flag attached to a word, indicating its role and relationship with other words in the sentence. So, regardless of the order, every word, with its own special ending, gives us hints about what it’s doing in the sentence, making it easier to understand quickly.

In the short story, the heptapods reveal that they know an entire sentence before it is written down. Instead of writing each element following the other, they write all of them simultaneously. As Louise learns this language, she realizes that it allows for more flexibility of thought. The English language is constraining for a species with simultaneous mode of consciousness like the heptapods. It explains why their language evolved that way.

Towards the end, it affects her way of thinking. She learns how to write without planning every stroke ahead of time. She sees ideas form in her mind’s eye as semagrams rather than words. Finally, her perception of time is no longer linear; she experiences future events alongside the present and understands her life as a whole rather than a sequence of moments.

References:

- Based on Lecture 03: Sentence construction and its underlying logic by Prof. Anuradha Choudry, IIT Kharagpur.

- Stories of Your Life and Others by Ted Chiang. This short story was made into the movie Arrival.