In 1132 CE, in Mangalore, the Tunisian Jewish merchant Abraham bin Yiju married Ashu Nair, a local Malayali woman. They lived together for less than two decades in great prosperity and raised a family. Eventually, their story ended in a heartbreaking tragedy. Fortunately, we can reconstruct the lives of these two people with a fair amount of accuracy because letters written by Abraham still exist.

Historical accounts typically concern kings, warriors, philosophers, or world travelers. Rarely do you get the stories of people like Abraham bin Yiju, who was one of the many traders along the Indian Ocean supermarket. We know about him because of an ancient Jewish tradition: if the form of the word God appeared on paper, it was not to be destroyed. A room called the geniza was maintained next to a synagogue to preserve such letters. This room had no doors or windows but a slot through which letters could be deposited. Abraham’s personal and business correspondence was preserved in a synagogue near Cairo.

This story is fascinating in many ways because we have first-hand accounts of the lives of Abraham and Ashu. Second, it gives us details of the ports of the Indian Ocean trading network and their inner workings. Third, it provides us vivid details of life on the Malabar coast at that time. We will learn about all these as we go over the lives of Abraham and Ashu.

Tunisia, Aden, and Cairo

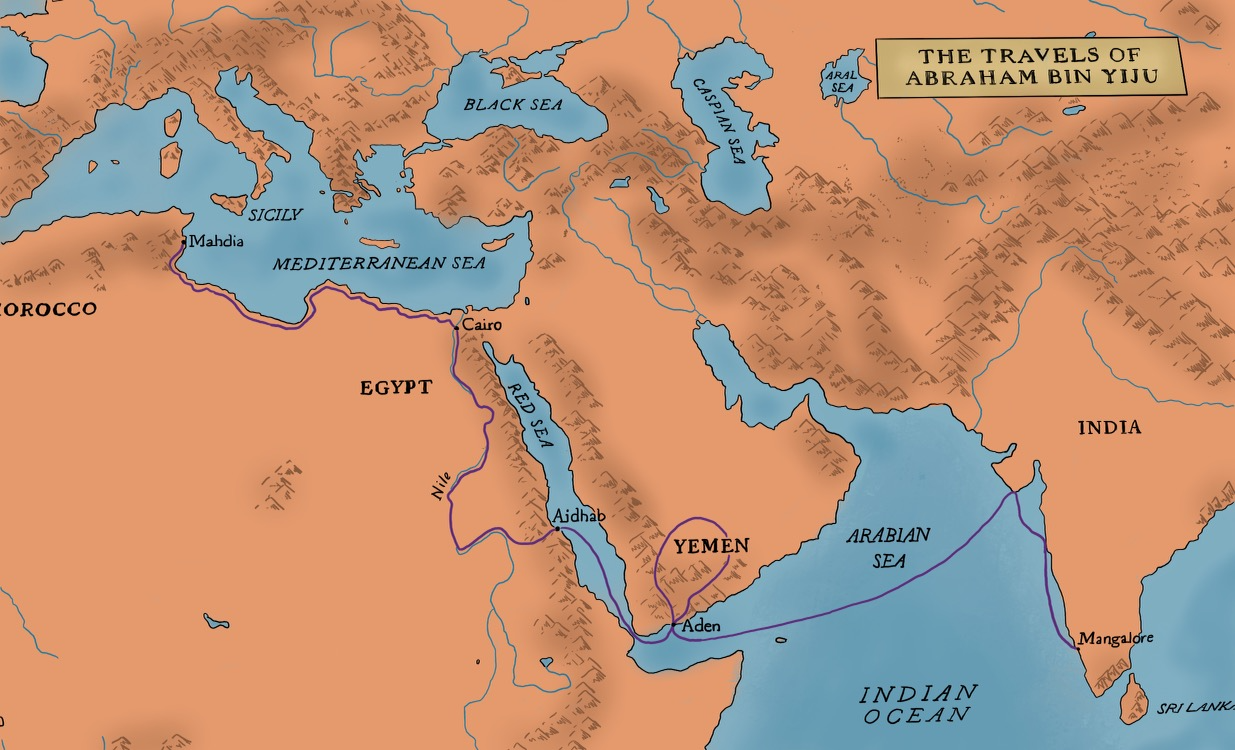

First of all, how does a Tunisian Jew end up on the Malabar coast in the 12th century and end up staying for two decades.? Abraham’s father was a rabbi in the port of Mahdia in Tunisia. Instead of becoming a rabbi, Abraham wanted to be a trader. The way to get a start in those days was by becoming an apprentice to a well-known trader. For that purpose, around 1120 CE, Abraham left Tunisia. He traveled along the caravan route to Cairo with letters of introduction to prominent Jewish Tunisian traders. Cairo was the hub from where spices were distributed to North Africa, Europe, and the Middle East. Abraham was on the move after spending a few years with traders there. He left for Aden with introductions to the Jewish traders there. The unfolding of his life was beyond prediction.

There was a reason why Aden was an important place. In those days, ships did not go directly from Malabar to Cairo. The stop before Cairo was Aden, a major conduit between the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean trade. The traffic to Europe via Cairo and the Middle East via Jeddah would go through Aden. Aden was also a perfect port location since it was where the spout of the Red Sea opened to the Indian Ocean. However, Aden had horrible weather and was cut off from the rest of the country via mountains. Hence, there was no hinterland to trade.

The Aden trading hub had one thing in plenty: traders with vast trading and travel experience. Though not as famous as world travelers like Ibn Batuta and Marco Polo, the trader Abu Sa’id Halfon had traveled between Egypt, India, East Africa, Syria, Morocco, and Spain. Another one, Abu Zikri Sijilmasi from Morocco, traveled to Egypt, southern Europe, and India. Traders like them transported Persian Saffron to China, dishes from China to Greece, Greek brocade to India, Indian steel to Aleppo, glass from Aleppo to Yemen, and striped material from Yemen to Persia.

There was a reason why Jewish traders in Cairo and Aden focused on the India trade. By this period, the First Crusade had taken over Jerusalem and established kingdoms over today’s Israel and Lebanon over the years. These “holy wars” made it difficult for Jews to work there as Anti-Semitism was rampant. Hence, European Jewish refugees moved to other opportunities like the India trade.

In fact, the existence of this long-distance Indian Ocean trade is not surprising at all as there has been plenty of evidence for commodities from India appearing in faraway places, even further back in time. Archaeologists in Dhuwelia, a seasonal hunting site in Eastern Jordan, found a cotton thread embedded in lime-plaster dating to the fourth millennium BCE. Cotton is not native to Arabia, and that particular species could have come from only one place in the world – Balochistan, where it has been cultivated since the fifth millennium. Queen Puabi, who lived in Iraq during the Mature Harappan period (2600 – 1900 BCE) had Harappan carnelian beads in her tomb. Following her, Sargon of Akkad (2334 – 2279 BCE) boasted about ships from Meluhha, primarily identified with this Indus region, docked in the bay. This suggests ships from the Indus region journeyed to Iraq about 5,000 years back.

Burial sites in the third millennium BCE Mesopotamia had shell-made lamps and cups produced from a conch shell found only in India; Early Dynastic Mesopotamians were consumers of the Harappan carnelian bead. By 2000 BCE, the trade between Africa and India intensified. While crops moved from Africa to India, genetic studies have shown that the zebu cattle went from India via Arabia to Africa. Around 1200 BCE, among the dried fruits kept in the mummy of Ramses II’s nostrils was pepper from South India. If you are familiar with the trading hubs of the old world (1, 2), there is nothing unusual about this trade from both North and South India.

The most important trading goods in the 12th century were spices, like during the time of Queen Puabi and Ramses II. Among the spices like cardamom, ginger, coriander, nutmeg, and cloves, black pepper was considered the most valuable. In 408 CE, Alaric demanded 3000 pounds of pepper as ransom from Rome. Pepper was not used just for cooking but also as medicine.

At Aden, Abraham found luck with one of the most powerful and influential Jewish traders named Madmun ibn Bandar. Madmun was the head of the city’s large and wealthy Jewish community and a man of great influence with a trading network extending from Spain to India.

Staying at Aden, Abraham mastered the intricacies of the Indian Ocean trade. He learned about the wind patterns which decided the trade cycles. He learned how to manage risk. Bad weather could sink a ship. Pirates could loot a ship. The risk was managed by spreading consignments across multiple ships, forming partnerships, and dealing with various commodities. During those times, no brokerage firms or warehouses could store goods for a fee. The traders kept track of the price fluctuations of iron, pepper, cardamom, and other spices in the markets of Cairo. They relayed the news to their friends and junior trading partners and kept track of events in Syria and Palestine.

As any marriage counselor would say, constant communication is crucial to success. There was a reliable mail system between the trading ports, which would allow a shipper to send advance notice of the list of goods before sending it on a ship. The mail system did not carry just the list of goods but also gossip and market intelligence. Trade depended on the goodwill of friends and business contacts. These relationships had to be established and nurtured. Hence, the letters also carried mention of personal affection for the recipient and their family members. Gifts were sent along with letters to keep the relationship strong.

Mangalore

After three years of apprenticeship, Madmun encouraged the young Abraham to move to Mangalore to become his junior partner in trade. Initially, this looked like a straightforward ask, but something else was happening here. Most traders traveled back and forth between the ports of the Indian Ocean. Some stayed for a longer duration, but none matched the length of Abraham’s stay at Mangalore. He stayed there for 17 years without even a trip to Aden or Cairo. It is possible he was a bad boy and ran to India to escape the repercussions or he had accumulated large losses and had to stay to recoup it.

The travel was not easy and he wrote about the hardships. Madmun reassured him that the wealth he would accumulate would compensate for the ordeal. The place where he arrived, Mangalore, was one of the many ports on the West Coast of India that rose to prominence due to the spice trade. The harbor was scenic, with the Nethravathi River flowing amid coconut trees into the Indian Ocean. A sandbar protected the lagoon from the ocean waves. Far away in the inland hills grew black pepper and other spices.

The time that Abraham moved to Mangalore was a time of honest trade. Twelve Hindu kingdoms on the Malabar coast controlled ports such as Mangalore, Beypore, Cochin, Cannore, and Calicut. The primary income for these kings was taxes on the trade and some of the wealthy financed ships. The king also provided protection from pirates while the ship was at the port. They also kept war fleets to attack pirates and force the merchants to pay taxes. Merchants stored their wares in fortified houses behind the harbor, close to the beach, where they could keep an eye on the incoming ships. There were no guns or walls or any other defense. These would change centuries later when the Asuric Portuguese showed up with the canons.

Abraham bin Yiju lived alongside a huge community of traders who were Arabs, Gujaratis, Tamils, and Jews. Like the Jewish traders, Gujaratis traveled across the Indian Ocean ports from Aden to Malacca. They had powerful control over the flow of goods. Madmun, Abraham’s mentor at Aden, had a close relationship with them and exchanged information about market conditions in the Middle East. Madmun had business relationships not just with these Gujarati traders but also with Muslims. Besides that, one of the ships he used belonged to a Pattani-Swami and a man called Nambiar, who was from Kerala.

Trade did not happen via the barter system. Gold and Silver came in from Aden. Abraham bought goods and sent them over to Aden; horse, weapons, and ceramics trade had not started yet. Goods that were imported to India consisted of silk and clothing, jewelry, household utensils, cheese, sugar, raisins and olive oil. The goods were imported in small quantities indicating it was for personal use and not for wholesale.

Also, the trading network was self-regulated, unlike in Europe, where guilds controlled it. There is no evidence of price regulation which existed in Europe at that time. Even though there were Hindu, Muslim, and Jewish traders, partnerships were conducted across religious lines. The biggest fear for the traders was not Jewish courts or Sharia courts but the loss of reputation. This prevented fraud more than the legal repercussions.

The Indian Ocean trade was so lucrative that one could become wealthy beyond imagination. One Muslim trader, Ramisht, profited so much from just one voyage that he provided Chinese silk covering for Ka’aba. Abraham, too, became wealthy. He imported soap and sugar from Egypt, pots and sieves from Aden, mats from Somalia, and carpets from Gujarat. His clothing, including robes, turbans, and shawls, was imported from Egypt.

Abraham also turned into an entrepreneur. There were many metal workers along the Malabar coast, and he saw an opportunity to start a repair shop. From his contacts, he received damaged vessels, lamps, and dishes from as far away as Spain. These damaged goods came with instructions for repair. This is an example of outsourcing work to India, a millennia before it became a thing.

There is one interesting point in his letters. Even though Abraham lived in Mangalore and never traveled to other ports or even inland towns, he referred to the region as al-Hind or bilad al-Hind (the country of India). Thus, even though many kingdoms along the Malabar coast controlled the various ports, even a 12th-century trader knew they were all part of India. Traders from that period knew the land east of Sindh to Assam as one unit called al-Hind. Arab travelers and geographers believed this al-Hind had one center under the control of a king named Ballahra (possibly the Arabic version of Vallabharaja, a title used by various dynasties). For them, Bharat was a civilization state.

Life was going fine when something happened on 17th October 1132 CE. The letters say Abraham publicly granted freedom to a slave girl named Ashu. Or words to that effect. The letters also tell us that Ashu was a Nair. Such relationships were common among traders who did not bring their families along. If you look at Ibn Batuta’s life story, he was the Sanjay Dutt of those times. Abraham married Ashu and had three children: a son named Surur, a daughter named Sitt Al Dar, and one child who died.

It is hard to believe Ashu’s backstory. Nairs were mostly warriors and some headed local kingdoms. Some of them looked after land and temples. Thus, it is hard to believe that a Nair would be enslaved. It is not like there were no Jewish girls on the Malabar coast then, and Abraham could have married one of them. Several thousand Jews lived around Cochin, but most were from Syria, not Tunisia. So, there was something else to the story that can be pieced from other information.

There is one incident which throws some light on what could have happened. Abraham had ordered 14 mithqals of cardamom from a middleman. The trader did not show up in time, and the ships were about to leave. So he had to buy cardamom for 17 mithqals. This was the nature of trade during that time. It was based on an understanding that allowed traders to commit large amounts of money without a mechanism to address fraud. Trust and relationships were paramount.

This was a fraud from the middleman. It was not just Abraham’s money at stake. Some of his partner’s money was also lost in this deal. Two of them wrote back, asking Abraham to deal with this matter directly, or they would rebuke the middleman. They also suspected that there was something odd in this transaction. They asked Abraham to deal with it directly, independent of the role of the partners. They pushed Abraham for many years, but no result came of it. It turned out that this middleman was a close relative of Ashu’s brother, the Nair. Thus, Abraham may have loaned the middleman because Ashu or her brother had asked him to. In such close business relations, it is possible that a monetary debt to her brother, who holds an important position in the matrilineal society of Nairs, may have forced the marriage.

This marriage, which went outside the Jewish community, was not accepted by the partners, and there is complete silence in the letters about Ashu. It is typical for the partners to inquire about the well-being of the merchant’s family. The problem could have been religion; according to Jewish law, the child gets the mother’s religion.

Malayali historian Manmadhan Ullattil, too, does not believe the slave story. He writes

My belief was that this deed was made by Yiju for the only purpose of making the Yiju offspring legal in their Jewish community back home and ensuring legal succession (Yiju was a wealthy man). I am not sure about Nair slaves (consider also that Ashu was not thrown out of home or lost caste- as she had a fruitful relationship with her family all the time) at that time or that Ashu would have wanted such a manumission document. Ghosh in his book the Imam and the Indian Page 220 concurs with this since the event was celebrated with fanfare, the document (like today’s wedding card!)was more a public announcement of the betrothal and legality than an act of manumission.

Abraham, Ashu and the Genizah

Final Days

Abraham would have lived on the Malabar coast with Ashu and the kids, but the actions of Roger II, the king of Sicily, changed their lives. In 1148 CE, Roger II attacked Tunisia. People were struck by famine and disease. Abraham’s family was kidnapped and taken to Sicily. Abraham got a message that his brother Mubashshir wanted to join him in India.

On this news, Abraham left Mangalore with his kids in 1149 CE. Ashu stayed or was left behind. Abraham met his brother, who defrauded him. His son Surur died soon after. In 1151 CE, Madmun, too, passed away. A broken Abraham moved from Aden to Egypt and south Yemen, where he became a prominent person in the Jewish community.

He got his daughter married to his elder brother’s son in Egypt. The daughter of a Nair woman, Sitt al-Dar, from Malabar, married her cousin at Futsat on 11th August 1156 CE. That way, Abraham’s wealth stayed in the family. During his final days, he stayed near his daughter. Abraham’s son-in-law, Perahya, made a meager living in the Egyptian countryside, which shows that Abraham was not as wealthy as he was in India. There was not really much wealth to preserve.

He never returned to Ashu in Mangalore. After the wedding, there is no news of Abraham. Neither his son-in-law nor other nephews mention him in their letters. Did he return to Ashu in Malabar or die alone in Egypt? We may never know.

PS: Two hundred years after Abraham bin Yiju, Ibn Batuta from the neighboring Morocco too made his way to the Malabar coast.

References

- When Asia Was the World: Traveling Merchants, Scholars, Warriors, and Monks Who Created the “Riches of the “East” by Stewart Gordon

- In an Antique Land by Amitav Ghosh

- India Traders of the Middle Ages by Shelomo Dov Goitein and Mordechai Friedman

- Abraham, Ashu and the Genizah by Maddy’s Ramblings

.

Name the ports where from Harrapan were trading with Arab and Tunisia