Sardar Udham, one of the most heartbreaking movies made on Jallianwala Bagh, was not sent to the Oscars.

Explaining why Sardar Udham was not selected, Indraadip Dasgupta, one of the jury members, told Times Of India, “Sardar Udham is a little lengthy and harps on the Jallianwala Bagh incident. It is an honest effort to make a lavish film on an unsung hero of the Indian freedom struggle. But in the process, it again projects our hatred towards the British. In this era of globalization, it is not fair to hold on to this hatred.”

Sardar Udham shows hatred towards British, jury on not sending film to Oscars. Fans are furious

Among the British atrocities in Punjab, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre is the most infamous. I recently read the book The Case that Shook the Empire, which lists many more of these atrocities.

Let’s go through some of them.

The British unleashed terror in Punjab as part of meeting the army recruitment quota for World War I.

The committee also recorded that men were captured forcibly and marched off for enlistment. Raids took place at night and men were forcibly seized and removed. Their hands were tied together and they were stripped in the presence of their families and made to bend over thorns when they were whipped. Additionally, women were stripped naked and made to sit on bramble bushes and thorn bushes in the hot sun until their men who had been hiding agreed to be recruited. In some instances, the women were made to sit with bramble between their legs overnight. Old men, too, had inhuman punishment meted out to them – they were made to sit ‘bare buttocks’ on thorns in order to force their sons to enlist.

The Case that Shook the Empire

In April 1919, Marcella Sherwood, a Church of England missionary, was allegedly attacked by a crowd as she cycled down a narrow lane. She had shut the schools and sent the kids home. While cycling through a street called Kucha Kurrichhan, she was caught by a mob, pulled to the ground by her hair, stripped naked, beaten, kicked, and left for dead. The father of one of her students rescued her by talking her to Gobindgarh Fort.

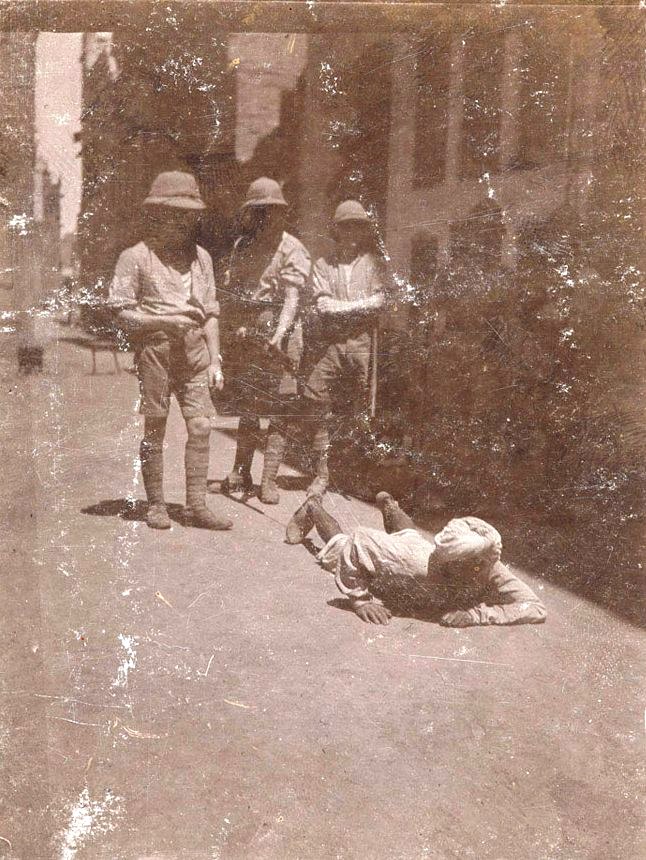

Reginald Dyer, the butcher of Jallianwala Bagh, met Miss Sherwood and ordered that every Indian man using that street must crawl its length of 150 to 200 yards on his hands and knees. Dyer explained his rationale for the order, “Some Indians crawl face downwards in front of their gods. I wanted them to know that a British woman is as sacred as a Hindu God and therefore they have to crawl in front of her, too… It is a small point, but in fact “crawling order” is a misnomer; the order was to go down on all fours in an attitude well understood by natives of India in relation to holy places.”

Many houses were alongside the street, and residents had to crawl to get their daily chores done. No one was exempt — the old, sick, the weak; everyone had to crawl. Of course, the crawl had to be perfect as well. If anyone lifted their bellies or turned to get relief from pain, the police would push them down with rifle butts. In his mercy, Reginald Dyer kept the order only from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. After 10 p.m., they were free to move about normally, except they would violate the night curfew and get shot.

On top of this, Reginald Dyer also ordered that any Indian who came within lathi-length of a British policeman be flogged. To facilitate the punishment, a flogging booth was built. Six boys were caught and given 30 lashes. When one of the boys, Sundar Singh, lost consciousness after the fourth lash, he was doused with water, and the lashing continued. He lost consciousness again, but he was lashed till the count of 30.

The next one was the salaam order. On seeing that the people of Gujranwala did not show respect to the British, a special order was issued. If the salute did not meet the expected standards, severe punishment was melted out. If the salaam was not performed by mistake, the turban was taken off his head, tied around the neck, and dragged to a military camp to be flogged. One person was even made to kiss the boots of an officer.

If they did not get an opportunity to torture, they spent their time humiliating people. Lawyers were made to work as coolies as punishment for protesting against the Rowlatt Act. The lawyers were humiliated in front of people who held them in esteem. A 75-year-old lawyer Kanhya Lal was made to carry furniture and patrol the city in the hot sun.

Immediately after Jallianwala Bagh, the administrator of Gujranwala asked for assistance. When he was told that troops could not be sent immediately, guess what was done – a bombing of the civilian population. Military bombers flew over the city and dropped bombs on random targets. A total of 12 people were killed and 24 injured in the bombing raid. The justification for the bombing of school children and farmers – “It was done to have a sort of moral effect”

The movie Udham Singh exposes only one of the atrocities committed by the British. There was no end to slaughter and torture, and the action was close to genocidal. Much of our forgotten history needs to be told, like Operation Red Lotus, Kashmir Files, etc. The old adage goes, “those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it.” The characters of the past and the stories we tell ourselves about them shape our present and future.

There is another kind of self-censorship in the world. The country which lectures the world on freedom, democracy, and minority rights censors itself to please China. Why would American film studios voluntarily run a Chinese Ministry of Truth in Hollywood.? Money.

But accessing those Chinese screens required the approval of Chinese censors, so studio chiefs in Los Angeles started to think like Ministry of Propaganda apparatchiks in Beijing. They scrubbed scripts of any scene, image, or line that might anger officials, avoiding at all costs the “three T’s” (Tibet, Taiwan, Tiananmen) or flashpoints like ghosts (too spiritual), time travel (too ahistoric), or homosexuality (too immoral). Behind-the-scenes changes became common: Red Dawn was only released after editing out a Chinese antagonist; World War Z was revised to cut implications that a zombie pandemic had originated in China; and Bohemian Rhapsody shoved Freddie Mercury back in the closet before Queen fans in China could see his story.

‘Top Gun’ Tells The Whole Story of China and Hollywood

When Avatar made $200 million in China, it was evident to Hollywood that crawling in front of Chinese censors could make them rich. So they have been doing that since.

Now, India does not need to please the British. They did not even ask for censoring the movie. For all these years after independence, we learned more about our invaders than our heroes. It was history written by the victors. When it’s time for us to tell our stories, it’s shocking that enslaved minds still exist after seven decades of independence. The British have left, but Indraadip Dasgupta is still crawling on all fours at Kucha Kurrichhan.