- Lime plaster fragments found in Dhuwelia (Eastern Jordan), around 4000 BCE had remains of a cotton fibre attached to it. The only place from where that particular sample of cotton could have come was Baluchistan[1].

- Some time after 2334 BCE, Sargon of Akkad boasted about ships to India lying in his harbor[1].

- After 2000 BCE, Indian cattle reached Africa and lived up to their name: the humped cattle. [2]

- On July 12, 1224 BCE, Ramses II, one of Egypt’s greatest Pharaohs died. When he was mummified, the priests put a couple of peppercorns from Kerala up his large bent nose[3].

In “Hubs of Medieval trade” (Pragati, June 2009), Ullatil Manmadhan wrote about the maritime trade networks in the Indian Ocean which between 1000 – 1500 CE transported goods, religion and culture from East Africa to Egypt to Arabia to India through ports like Calicut, Fustat and Ormuz. But many millennia before this — before the urban dynasties of Egypt, Mesopotamia and Harappa — there existed a maritime network which linked Africa to India via Arabia.

|

| (Cotton) |

There are few issues when you go that far back in time: we don’t have historical records, remnants of trade artifacts, or representation of those activities in art. While travelers like Marco Polo or Ibn Battuta left us narratives of their travel, we don’t have that luxury while dealing with this period.

In the absence of the written record, the story has to be constructed from genetic studies, studies of plant and animal dispersal, and by archaeology. For example, much of the domesticated plants and animals in Arabia originated outside Arabia: cattle was introduced from the Near East and donkey from Egypt. Regarding plants it is possible that the date palm in Arabia probably came from the Indian Sugar Date Palm or from Iran around 5000 BCE.

The history of this trade network starts in 6200 BCE for a reason. In the time period between the rise of farming communities and the peak of Harappan civilization, 6200 BCE was a dry period. Following this dry period sea levels rose and water was released from various lakes into the Atlantic and Red Sea affecting the coastal sites. Thus if coastal communities existed before that period, the evidence is hard to find.

The evidence for coastal communities come from shell middens, which are shell mounds. Shell middens can reveal a lot of information about human activity including the food they ate. Some of these mounds were the place where the village would dump garbage and some times contained evidence of house hold goods. The Greeks called the beach dwellers Ichthyophagi — mainly to the stump the finalists of the National Spelling Bee — and after 6200 BCE, there is a rise shell midden sites around Arabia.

Once coastal communities were established, the next step was maritime trade. But sea faring was not an easy task: the sailor, besides having knowledge of the currents, also had to be an expert in navigating past shoals and reefs. They also had to know when the wind blew north so that they would not waste time traveling south.

Arabian people of this period knew about ocean traveling; the remnants of a boat was found near Kuwait and this boat which was made from reed bundles, tied with rope, and sealed with bitumen had barnacle impressions on it. This site, which could be dated to 5500 – 500 BCE, also had a painted disc showing a sailing boat[4].

The Egyptians used boats even earlier; there has been evidence of boats on the Nile dating to the 7th millennium BCE. Egyptian trade started around 5000 BCE and maritime trade a millennium later. This was the time around which the Persian Gulf and Red Sea trade started as well.

India enters into this network around the fourth millennium BCE. Archaeologists in Dhuwelia, a seasonal hunting site in Eastern Jordan found cotton thread embedded in lime-plaster. Cotton is not native to Arabia and that particular species could have come from only one place in the world: Baluchistan, where it has been cultivated since the fifth millennium[2]. But it is not clear if this prized good was transported via a land route or on a boat to the Persian Gulf. One thing is clear;to reach Dhuwelia one has to travel through the Euphrates valley[3].

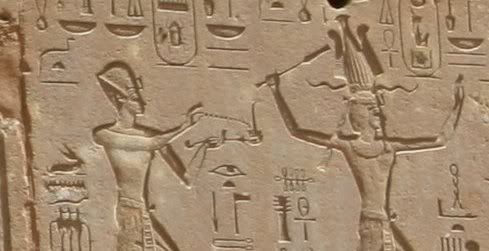

|

| (An Akkadian ruler, probably Sargon) |

After the mid-fourth millennium BCE, the world changed. The urban civilizations of the Old World started rising – in Mesopotamia, in Egypt, in the Indian subcontinent. These civilizations maintained records which reveal more about the trade networks and the maritime activities. This is the time when places like Dilmun (Arabian Mainland or Bahrain), Meluhha (Indus), Punt (somewhere in Africa) came into existence in records. With the rise of urban societies, the goods started traveling farther and trading networks developed.

By this period, the Egyptians moved from reed to wooden boats and started using the sail. Like the 14th century Ming emperor who sent out huge fleets for prestige and power, the fourth millennium BCE Egyptians too started doing the same. Like Zheng He’s fleet, these ships too were spectacular and went around acquiring exotic goods. Wood was imported; there were break throughs in sail-rigging; the Egyptians were soon making sea voyages to Punt.

By the time of Mature Harappan, there is evidence of direct trade between the participants. Around this time the Sargon of Akkad (2334 – 2279 BCE) boasted[1]:

The ships from Meluhha

the ships from Magan

the ships from Dilmun

he made tie-up alongside

the quay of Akkad

Another Sargonic tablet mentions an Akkadian who was the holder of a Meluhha ship and a seal mentions a person who was a Meluhha interpreter. Indus seals — the ones we have been applying the Markov model on — too start appearing in Mesopotamia.

Notes:

- Coming in Part 2: trade with Mesopotamia and East Africa

- The primary source for this article is a recent paper: Shell Middens, Ships and Seeds: Exploring Coastal Subsistence, Maritime Trade and the Dispersal of Domesticates in and Around the Ancient Arabian Peninsula by Nicole Boivin and Dorian Fuller.

- Images from Wikipedia